Diagnosis: Projection

Most films that fall under the Projection diagnosis category are action/adventure type films. I’ve had a tough week at the office. My boss is pressuring me to produce or perish. I’m pretty sure my fifteen year old is smoking pot in his bedroom after dinner; what’s worse, I want to join him. What do I need? I need to watch John McClain battle terrorists at the

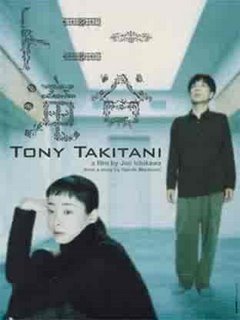

But there is another side to Projection films, a more sobering side. These are the films that appeal to the weaker aspects of ourselves. When we identify with the protagonists in these films, we are reminded of the lesser things we might become. These films should give us pause, looking at the turns in our lives that might have lead us to barren fields and irreparable damage. Tony Takitani is one of these films.

This film is particularly recommended for those patients who suffer from either haughtily inflated egos or perilously deflated ones. For those inflated patients, this film serves as a mirror for those basic desires of life, love and companionship. Patients who are too self-satisfied ought to watch this film as a reminder of the ways that things can go amiss, even when things seem at their strongest.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, patients suffering from deflated egos ought also partake in this film. For patients already hypersensitive to their personal tragedies, this film acts as a reminder that memories should be bittersweet, not only one or the other. Remembering only the low points can destroy a life; remembering only the highs can make those memories hollow.

Prognosis: * * * *

Psychologically speaking, this film does an excellent job satisfying a psychological need that can be satisfied by a number of other films. There are other films that evoke the sort of psycho/emotional response that this film does.

That being said, this is a beautiful film. What makes this movie noteworthy amongst its peers is its style. Based on a short story by Haruki Murakami, the film has a strangely narrative style, employing a great deal of voice-over throughout. This allows viewers to feel as a third-party observer throughout the film, always maintaining a psychiatrist’s objectivity and distance. Viewers, therefore, have a unique opportunity to see the trials and tribulations of the characters from a clinical perspective without being a clinically oriented film. This film could have easily been told without the narration and been a more conventional experience, but it would have lost its sense of objectivity. Viewers would easily have been drawn into the characters’ emotional states, making analysis more difficult.

The analysis of this film ought to be primarily reflective in nature. It is recommended that viewers pay close attention to their own reactions to the events of the film. These reactions will be key in the digestion of this film after the fact.

Synopsis

Tony Takitani (Issei Ogata) has been an outcast his entire life. The son of a Japanese jazz man, Tony was a shy boy who blossoms into an awkward adult. Tony’s life is quiet and methodical, filled entirely with his excellent, if limited, work as a technical illustrator.

As often happens, even to the strangest of people, Tony falls in love with Konuma Eiko (Rie Miyazawa), and they marry. These two are the happiest of couples, Tony engaged in his illustrations and Konuma engaged in her love of designer clothes. Though padded by Tony’s ample savings, it becomes clear that his wife’s obsessive shopping is a dangerous addiction. When confronted, Konuma readily admits to her addiction, not understanding her own desperate desire for beautiful things. Realizing that she is utterly unable to stop herself from shopping, coupled with the knowledge that her shopping will someday harm Tony, Konuma takes her life.

Tony’s life falls into despair and desolation. After a period of extreme isolationism, Tony takes an ad out in the paper, seeking a woman of his woman’s exact measurements to utilize his dead wife’s wardrobe. Tony finds Hisako (also played by Rie Miyazawa) to be his personal assistant, her only unusual job description being that she only wear the clothes from his wife’s closet. Tony is completely up-front about his motivations and intentions; he has no desires beyond seeing his wife’s clothes full of life again.

As much as both parties want the new arrangement to work, Hisako finds herself overcome by the wardrobe, suddenly becoming part of someone’s most treasured possessions. Could such an arrangement last? Probably not, but that is hardly the point. This is a film about love and its replacements, and, in the end, all replacements are temporary.